Vital Signs, Missed Signals: A Fetal Monitor Delay and Its Legal Fallout

Case #22 A Birth Injury, a Federal Hospital, and the Fight Over When to Intervene

A Missed Window

In the early morning hours of March 11, 2014, a 32-year-old woman arrived at a Massachusetts hospital in active labor. She was 39 weeks pregnant. Over the next several hours, her medical chart documented a pattern of fetal heart rate decelerations — first variable, then more prolonged. According to the plaintiffs, the signs of fetal distress were mounting. Yet, instead of moving quickly to deliver the baby, the care team opted to continue monitoring.

In expert reports submitted during litigation, Dr. SM later opined that the fetal monitor tracings in the 50s may have reflected an arrhythmia — not true bradycardia — and therefore would not have required the same intervention. The arrhythmia had been audibly noted during the day, and the case was reviewed with a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist in the afternoon. A plan was made at that time to have neonatology present at delivery.

It wasn’t until more than five hours after an MFM specialist had recommended applying a fetal scalp electrode (FSE) that one was finally placed. Fetal scalp electrodes are often used when external monitoring is insufficient or tracings are unclear — a critical step that, in this case, was significantly delayed.

By then, the fetal heart rate had dropped significantly. The baby was ultimately delivered via emergency cesarean section at 1:48 a.m. on March 12, 2014.

He was limp, blue, and not breathing. The APGAR scores were 0 at 1 minute, 0 at 5 minutes, 4 at 10 minutes, 5 at 15 minutes, and 5 at 20 minutes. Cord blood gases showed severe acidemia (umbilical cord pH 6.81). He required chest compressions, intubation, and epinephrine during resuscitation. A normal saline bolus was administered at 15 minutes of life to support oxygen saturation.

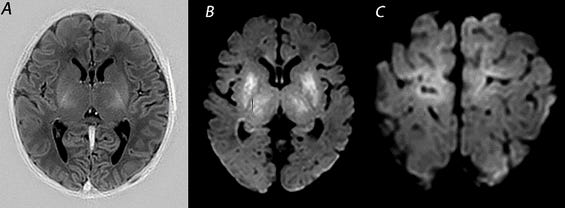

He was then transferred to the special care nursery and later to Tufts Medical Center, where he was diagnosed with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE). At Tufts, he underwent an MRI showing diffuse cortical mantle injury and T1 hyperintensity. A long-term EEG showed severe diffuse neuronal dysfunction, though no seizures were captured at the time. He was placed on phenobarbital. His head circumference at birth and on subsequent exams remained at 33.5 cm (37.5th percentile), and was later measured at 35 cm by May 19, 2014, consistent with acquired microcephaly.

This type of injury — affecting deep brain structures during acute intrapartum hypoxia — is often captured on MRI within the first week of life.

He was hospitalized for the first two months of life and required multiple transfers between regional medical facilities. By the time of discharge in May 2014, his discharge diagnoses included seizures and neonatal encephalopathy.

By the age of four, his documented diagnoses included:

Spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy

Global developmental delays

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM)

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

He was non-verbal, but could understand much of what was said to him, and he was walking with the assistance of a walker.

The plaintiffs allege that the delay in monitoring and response — including the failure to place the FSE and escalate care promptly — caused their son’s brain injury. The government argues the timeline reflects appropriate, cautious care under uncertain circumstances.

What the Literature Says About FSE Timing and Missed Intervention

The delay in placing a fetal scalp electrode (FSE) in this case raises an important question: what do clinical guidelines and studies say about the timing of internal monitoring when external tracings are unclear?

FSEs are recommended when external monitoring is inadequate, particularly in cases of non-reassuring tracings, recurrent decelerations, or suspected arrhythmias. Clinical guidance emphasizes their role in clarifying fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns when decisions about escalation are pending.

The plaintiffs alleged that the five-hour gap between the maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist’s recommendation and actual FSE placement allowed fetal distress to go unrecognized, narrowing the window for effective intervention.

This concern aligns with current guidelines. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) notes that when external monitoring “does not provide interpretable tracings,” internal monitoring using a fetal spiral electrode should be considered, if available, to enable accurate assessment and timely clinical decisions. (1) Similarly, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises that “when external fetal monitoring is inadequate and a Category II tracing persists, placement of an FSE is an appropriate next step.” (2)

Although complications such as minor scalp abrasions, infections, and, in rare cases, fetal scalp abscesses have been documented with FSE use, these risks are generally considered low relative to the benefit of achieving continuous, accurate fetal heart rate data in high-risk labors. (3)

In the context of this case, the five-hour delay is striking. With an MFM recommendation already on record, such a prolonged wait may have conflicted with best practices for high-risk deliveries. For the plaintiffs, it became a central argument: not a failure to monitor, but a failure to act decisively when clarity was needed most.

A Four-Year Fight to Get to Court

The events of that March morning set in motion a legal battle that would stretch over a decade.

The child’s injuries were apparent immediately. Within months, the parents initiated a Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) administrative claim, alleging negligent labor and delivery management at a federally funded hospital, specifically, delays in monitoring and delivery.

Before filing suit in federal court, FTCA claimants must first submit an administrative claim to the relevant agency — in this case, the Department of Health and Human Services. That process alone can take many months. After the claim was denied, the plaintiffs filed suit in 2021.

But litigation moved slowly.

The government challenged expert reports, filed motions to dismiss portions of the complaint, and disputed discovery. Deadlines were extended. Depositions were delayed.

One of the earliest and most consequential battles centered on the statute of limitations. The government argued the lawsuit was untimely — that the parents should have recognized, earlier, the potential connection between the alleged malpractice and their child’s condition. The plaintiffs responded that they did not fully understand the cause of their son’s injuries until months later, when neurological evaluations and specialist consultations clarified the diagnosis.

The judge ultimately allowed the case to proceed. He emphasized that the legal clock begins not at the moment of injury, but when a plaintiff knew — or reasonably should have known — that malpractice may have occurred.

This dispute over timing set the tone for what would become a contentious case, marked by procedural complexity and conflicting expert opinions.

By 2024, the docket was dense with disclosures, motions, and thousands of pages of medical and legal records — all stemming from a delivery that had occurred ten years earlier.

What the Experts Said — And What the Court Had to Weigh

With the statute of limitations challenge defeated, the case moved forward, and both sides began assembling expert witnesses to battle one central question: what caused the baby’s brain injury?

The plaintiffs in PN v. United States retained experts to analyze whether the standard of care had been breached and to establish a causal link between the care provided and the child’s resulting brain injury. The government disclosed its experts to rebut those claims. These expert reports and disclosures, detailed in the record, offer insight into how the two sides prepared to argue the key questions of negligence and causation.

Plaintiff Expert Opinions

In a disclosure submitted by plaintiffs’ counsel, it was stated:

“Plaintiff will offer expert testimony regarding causation, damages, standard of care, and breach of the standard of care.”

The experts retained by the plaintiffs were expected to testify about:

The failure to escalate care after non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns was observed,

The timing and nature of the brain injury, and

The proper use and interpretation of fetal monitoring and nursing documentation.

One expert was expected to opine that the hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) experienced by the child was “most consistent with an intrapartum event,” and that earlier delivery would have avoided or mitigated the injury.

Defense Expert Opinions

The government disclosed expert witnesses in obstetrics, neonatology, and maternal-fetal medicine to rebut the plaintiffs’ claims of negligence and causation. Their reports challenged both the timeline and the interpretation of fetal heart rate tracings offered by the plaintiffs.

One government expert contended that the fetal heart rate abnormalities observed late in labor were consistent with an arrhythmia rather than true bradycardia, and that this distinction was critical in understanding the clinical decisions made. According to this opinion, the tracings were intermittently difficult to interpret due to signal loss, and care was appropriate given the information available at the time.

Another expert emphasized that there was no actionable indication for cesarean delivery until shortly before it was ordered, and that once the diagnosis of terminal bradycardia was made, the clinical team responded within a reasonable timeframe.

Defense experts also asserted that the baby’s neurological injury was not necessarily linked to intrapartum events, suggesting that earlier delivery might not have altered the outcome — a direct challenge to the plaintiffs’ theory of preventability.

One Expert, Multiple Roles?

One unusual aspect of the plaintiffs’ expert disclosures stood out: Dr. MK, an osteopathic OB/GYN, not only offered opinions on the standard of care for the defendant physicians, but also rendered formal conclusions about the alleged deviations by labor and delivery nurses. In his written report, Dr. MK repeatedly stated that specific nurses failed to meet the nursing standard of care, citing their missed opportunities to recognize abnormal tracings and escalate care.

That kind of testimony raises a procedural red flag. In medical malpractice litigation, expert witnesses are generally expected to testify only about the standards of care within their own profession. A physician testifying about what a “reasonably prudent nurse” should have done can be problematic — unless that physician has clear, relevant qualifications to speak authoritatively about nursing practice.

In fact, Dr. MK’s report explicitly details his criticisms of the nurses’ failure to recognize and act on abnormal fetal tracings — a task typically reserved for nursing experts.

Interestingly, the case record reviewed contains no motion in limine challenging Dr. Kushner’s qualifications to opine on nursing care. But since the case settled just weeks before trial, it’s possible that such a challenge was in development — or might have emerged had jury selection moved forward. Either way, it’s a strategic wrinkle worth noting for future cases involving cross-profession expert opinions.

Documentation Disputes and Timeline Reconstruction

From both sides, the expert disclosures and reports made clear that medical record interpretation would be a central battleground.

The plaintiffs planned to introduce evidence that the progress notes failed to capture worsening fetal distress in real time. The defense, by contrast, intended to rely on those same records to argue that appropriate surveillance and response measures were in place throughout labor. According to the government’s expert disclosures:

“Intermittent decelerations were managed appropriately with maternal repositioning and observation,” and no surgical delay occurred once a cesarean was indicated.

Legal Strategy: Motions and Limits

As the trial approached, both sides filed motions in limine — pretrial requests to limit or exclude specific evidence and arguments from reaching the jury.

The plaintiffs moved to block any suggestion of contributory negligence, particularly regarding the mother’s prenatal care. The government, in turn, sought to bar references to non-party fault and exclude mention of prior cases involving the VA.

These motions reflect a common litigation tactic: shaping the narrative before the first witness ever takes the stand. By defining what the jury can and cannot hear, each side aimed to frame the facts and avoid distractions that could undermine their core arguments.

One notable example: the government moved to exclude any reference to a separate, unrelated malpractice lawsuit that had been filed against its expert witness, Dr. Katherine McCleary. That lawsuit — brought by the same law firm representing the plaintiffs in this case — was still in its early stages and had not resulted in any findings. The government argued that allowing it into evidence would unfairly prejudice the jury and have little bearing on the credibility of her expert opinions.

The Quiet End — A Settlement and Its Implications

There was no finding of liability. No jury ever heard the evidence. But the litigation left behind a trail of depositions, disclosures, and medical records that speak volumes — not just about one birth, but about the broader fault lines in obstetric care and legal accountability.

The case never reached a courtroom verdict. It ended quietly, through a settlement finalized just weeks before the trial.

Court records show that on April 2, 2025, the case was dismissed with prejudice following a resolution between the parties. While the exact terms remain sealed, filings related to the child’s structured settlement and special needs trust suggest a total settlement of approximately $640,000, with funds earmarked for long-term care. One key document that emerged from the settlement process was the child’s irrevocable special needs trust, structured to ensure long-term eligibility for government benefits.

What remains is more than a closed case. It’s a case study in how medical decisions are later dissected in litigation, how documentation becomes legal evidence, and how families seeking answers often encounter a system that prioritizes finality over complete transparency.

For attorneys and medical experts alike, PN v. United States offers a lasting lesson: in birth injury litigation, the real case may be won or lost not in front of a jury, but in the charts, protocols, and timelines that shape how the story is ultimately told.

Need Expert Medical or Scientific Research for Your Case?

Contact me at librarian@grahammedlegalresearch.com to ensure your next case is built on solid research.

Website: Graham MedLegal Research, LLC.

References

Dore S, Ehman W. No. 396-Fetal Health Surveillance: Intrapartum Consensus Guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020 Mar;42(3):316-348.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.05.007. Erratum in: J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021 Sep;43(9):1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.07.008. PMID: 32178781.

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jul;114(1):192-202. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aef106. PMID: 19546798.

Kawakita T, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Iqbal SN, Huang CC, Grantz KL. Neonatal complications associated with use of fetal scalp electrode: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2016 Oct;123(11):1797-803. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13817. Epub 2015 Dec 8. PMID: 26643181; PMCID: PMC4899296.